We’ve discussed in great detail the versatility and nutritional value of fonio in recent articles, but one aspect of this super grain that still has many hurdles to clear is: how do you scale up the production and exportation of a traditionally difficult to harvest (and expensive to purchase) crop from a food insecure region, while simultaneously having a net-positive impact on the communities where it is grown and the grain’s end-consumer? At first glance, it sounds like a near-impossible task, but with the right approach, we have little doubts that it can be done. In our opinion, the main questions are simply around how, if and/or when fonio will impact the global food supply in a meaningful way.

In an attempt to answer many of these questions, we looked inward to the person here at Terra Ingredients who first introduced us to the idea of fonio and is now one of the leaders of our fonio initiative. That person is Malick Diedhiou, a Commodity Trader with Terra, who not only has extensive experience in trading grains internationally, but also has familial roots in West Africa. Malick is using his knowledge of the land, people, and his professional experience to help us enrich the lives of our customers and their consumers by being at the forefront of fonio’s gradual rise in popularity. More importantly, we are doing so by ensuring that we’re first enriching the lives of fonio farmers and their surrounding communities—who are also still the grain’s primary consumer.

We were able to recently sit down with Malick for an extensive interview to break down our current supply chain and the challenges that lie ahead for fonio. In this discussion, we cover everything from logistical, ethical, environmental, infrastructural, technological and geopolitical issues that must be faced in order to accomplish our goals in a sustainable, positive manner. See the full transcript of our interview below:

Fonio Supply Chain Interview with Malick Diedhiou:

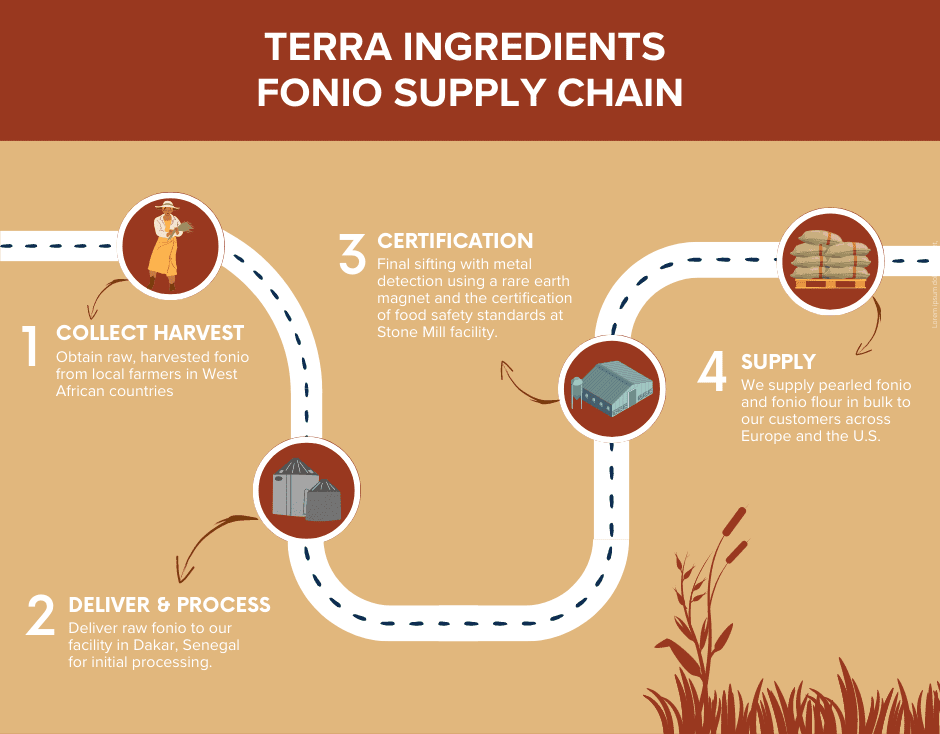

Q: What is the current step-by-step summary of Terra Ingredients’ supply chain for fonio?

Malick: “The basic structure of our fonio supply chain is:

- Obtaining raw, harvested fonio from local farmers in West African countries (Senegal, Mali, Guinea & others), then →

- Delivering the grain to CAA, our family-owned strategic partner facility in Dakar, Senegal for processing, followed by →

- Final sifting with metal detection using a rare earth magnet, which is currently done by Stone Mill, our GFSI-certified sister company in North Dakota. And finally →

- We supply pearled fonio and fonio flour in bulk to our customers, which are primarily located in Europe and the U.S.

Basically, we are removing the middle men/aggregators that often reduce the profitability of the farmer. Also, in six-to-nine months we anticipate that our local partner facility in Dakar will be FSSC/BRC-certified, which will eliminate the need to send all of our fonio through an additional processing step before we can deliver it to our customers. This will only further improve efficiency and reduce costs for the end-consumer, while also increasing profitability for the local farmers.”

Q: What were the logistical challenges we were faced with upon discovering the opportunity for fonio?

M: “In short:

- Crop size (the need for an increase in cultivated land)

- Processing, which has been solved via our Dakar processing plant, and

- Improved infrastructure in order to maximize the accessibility of fonio in places like Guinea, as well as the transportation of fonio between countries like Senegal and Guinea. Substantial amounts of fonio already pass between these two countries, but there is still room for improvement.

To point #1, it is important to clarify that what I mean by crop size is that we aren’t pushing for, nor do we see the need to create large fonio farms. Fonio is still primarily cultivated by smallholder farmers and there are no large fonio farms that exist currently—and we believe it should stay that way. Fonio is cultivated on a community/small-scale level and the key for us is to succeed in the aggregation of these small farms at a village level, not in creating large, single-owner farms focused solely on mass production.

The crops I saw when we first began investigating fonio were cultivated by independent farmers, where it’s basically a house and then a very small piece of land behind it where they were subsistence farming and growing crops for their own consumption. You don’t have these big chunks of several hundreds of acres of land on which fonio is grown, so in order to accumulate enough fonio for a full truck load—which is anywhere between 20,000 to 40,000 kilograms, or 20-40 metric tons—you have to accumulate it from 100, 150, or even 300 farmers. Logistically, this is one of our biggest challenges.

To solve this problem, what we’ve done is partner with whole villages in order to organize co-op style farming groups. Together, we’ve been working to create these single collection points where farmers can drop off their fonio harvest and receive payment based on the weight of their delivery. Thus far, we’ve only been able to do this on a very small scale, but as the demand for fonio grows, we envision this type of co-op style collection will need to be expanded. We would likely have to replicate the pilots we’ve been running in Senegal, (The Gambia) and Mali with more villages in order to create a supply chain that works for all parties involved.

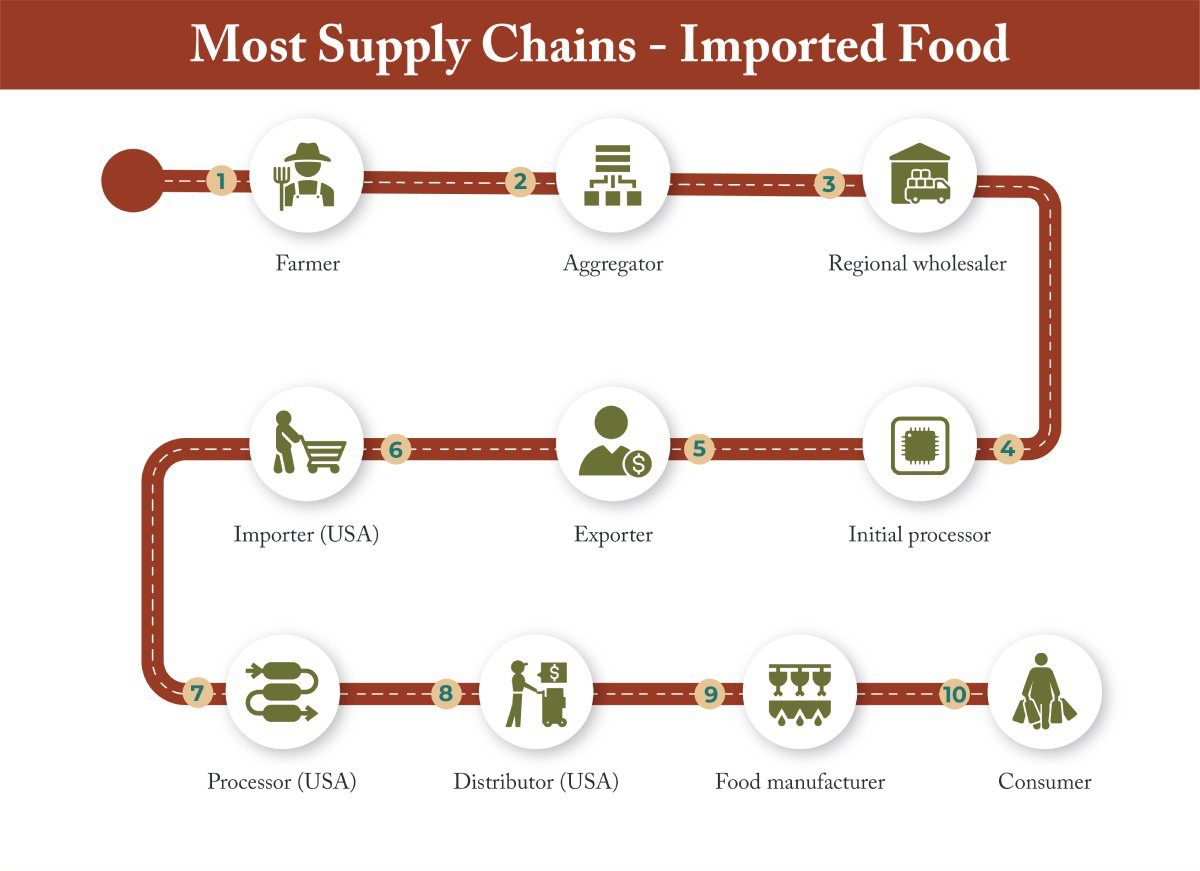

We believe it’s important to have a single collection point, because what is also possible is that you have a large number of wholesalers active in those countries, each having anywhere from five to 30 metric tons of fonio that you could just buy from them. These wholesalers are the ones who typically go from village-to-village to collect fonio, with two or three wholesalers often being involved in the supply chain before it (the fonio) then makes its way to an even bigger wholesaler. The problem with this model is that there’s a substantial amount of margin that is then kept between those different layers, instead of going directly to the farmers and their communities. Our idea is to remove those wholesalers and make sure that the farmers keep more margin in their pocket. Of course, this creates another challenge, but so far it has been quite successful.

The second challenge we’ve been confronted with is the lack of mechanization of farming techniques. Fonio is still harvested by hand with sickles and farmers spend a significant amount of time bent over during this process, making it a very tough job on the body. Additionally, this limits the output, depending on how much manpower is available when it comes time to harvest. There are threshers that remove the grain from the plant, but there are currently nowhere near enough threshers in every village. Without a thresher, farmers will instead put a tarp on the ground, pile the fonio onto the tarp, and then batter the fonio to remove the grain from the plant. As you can imagine, this process is also highly labor intensive. Lastly, you still have to process the grain, which includes removing the hull, cleaning out any sand from the grain and then drying it. Again, most of this is done by hand.

All of the steps I outlined previously are just an obstacle to greatly improving the output of a fonio harvest. For some of these issues there are already solutions, and it’s mainly about investing into and buying threshers so that every village is equipped with them. For other challenges, however, there are no solutions and more research is needed to resolve them. For example, it has yet to be figured out how to mechanize the cutting of the grain.

Lastly, the infrastructure issue is primarily in regards to the roads in many of the countries I’ve discussed previously. This includes not only road quality, which allows for large transport vehicles to haul fonio, but also driver safety due to violent conflicts in some areas where these supply routes have to pass through. There is also a shortage of storage facilities/grain silos. It’s not like what you have in the U.S., where you could go into the middle of rural Wisconsin and you can probably find a couple of grain silos or bins to rent.”

Q: What were the ethical challenges Terra needed to confront and resolve before moving forward with the fonio initiative?

M: “I think the ethical challenge is mostly a question of: how do you build fonio export channels out of countries that are food insecure, or that go through periods of food insecurity? The logic we’re applying to the issue is that fonio has never had a big market other than localized trade, thus, people were not necessarily incentivized to expand the acreage that would be grown with fonio, because there was simply no demand for it. By creating the demand, we hope to expand the acreage that can be cultivated, and by expanding the acreage and the overall output, you hopefully get to a place where people will be able to retain more fonio for their own consumption and export the remainder for profit—whether that’s within Africa from the demand that is hopefully being created in the Sub-Saharan countries, or to the U.S., Europe and elsewhere around the globe.

Additionally, if a farmer chooses to sell his or her entire crop, minus the seed stock that needs to be retained, they can then generate enough money to buy other goods. This logic and approach that we’re applying is in line with the IFC (International Finance Corporation), who have done their own research and hold the same viewpoints as we do.

Of course, food security is something that needs to be continuously monitored and we need to pivot if there’s a warning sign that it’s not working. This will come with the requirement to work with NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations) on the ground that are monitoring the situation in real-time, and others that specialize in food security challenges. We have been in contact with the WFP (World Food Programme), who provide updates on marketplaces and are checking the prices of fonio week-by-week to see, 1) is it getting too expensive for people to buy staple crops or not, and 2) what’s the availability of it on the markets? They are essentially mapping food insecurity patterns throughout the regions we are focussed on, so by working hand-in-hand with them (WFP) and other experts on the ground, we should be able to collect all of the most critical data and pivot if needed.”

Q: So, is determining the viability of scaling up fonio still not 100% solidified? For example, one of the problems with Quinoa is that local farmers eventually were priced out of the market. Could the same thing happen with fonio, or is it even possible to scale fonio to that level due to its growing, processing and harvesting limitations?

M: “The tricky part of it, in my opinion, is that where fonio and quinoa are not a perfect match for comparison is that fonio is already four-times more expensive than rice. Thus, a farmer who sells one kilogram of fonio can buy four kilograms of rice, so in that sense, local populations are already priced out because fonio is so expensive. Expanding the cultivable areas should get the price down, making fonio more accessible locally and reducing the risk for acute food shortages. However, accessibility also depends on droughts and other factors.

Honestly, the ethical piece has many more layers to it. It’s not something I pretend to be an expert on, but we need to point it out and understand that our work here at Terra Ingredients is that we can’t just say, “we’re a food company and what we need to do is work on having a really efficient supply chain.” Yes, that’s the core job, but doing this project has a component of making sure that what we do creates a positive impact. That is why, by partnering up with experts, we will be making sure that all these points are being respected and that we don’t have a negative impact with this project. We purely want to have a positive impact with fonio.”

Q: What role does the Dakar facility, which was built for processing & dehulling, play in creating a more efficient supply chain?”

M: “To achieve scale and reduce variability in quality. The amazing thing is that it’s the only fully-automated processing plant for fonio worldwide. This has allowed us to increase scale and achieve standardized quality levels for fonio prior to exporting it from West Africa. Now we just need to continue to work to improve it and make it more efficient. I’m just super proud of what they’ve done in Dakar.”

Q: Who did we have to work together with (local gov’t, leadership, etc) in order to build this facility?

M: “We have a local partner company called CAA SA. They built and own the facility.”

Q: Was it difficult to get the Dakar processing facility built, or was everyone involved in the decision making on board?

M: “Everyone was on board, but it was still very difficult because what happened is we (Terra) made the decision to go ahead with the project in 2019, I believe, and the tricky thing is that half of the equipment now used in the facility had to be created since it simply didn’t exist yet. Whereas, if you want to build a wheat mill, a flax cleaning line, or a lentil cleaning line, all of that equipment you can order from Buehler and it has been in existence for I don’t know how long. As for fonio, it has not been that way, so how do you remove the impurities, how do you dry it, and everything else that goes into processing? I mean, it’s not as if grain dryers didn’t exist, but it’s more that you couldn’t just go out and order it from an equipment supplier as you would for every other crop.

So, the first six-to-nine months were just the conceptualizing and building of the equipment pieces that did not exist yet. Then, I think it was shipped in January or February of 2020, and in March of that year, Covid hit and there was no border crossing for an extended period. There was no way to get pieces from other countries, so that was completely on hold for six months. It was a lot of hoops to jump through, but now things are going very well. The next step will be to have the food safety certification in place at the Dakar facility, with either BRCGS or FSSC (Food Safety System Certification), and then at some point adding a flower line to allow for grinding of the fonio into flower in Dakar before exporting it.”

Q: Why did we choose Dakar, Senegal for the location of the fonio processing facility?

M: “Quite simply, due to the existing infrastructure and being strategically located near the port.”

Q: What is the nature of Terra’s partnership with Stone Mill and what is their role in the fonio supply chain?

M:“Stone Mill is our sister company (affiliate). Our customers require that product to go through a processing plant certified via an international food safety scheme and Stone Mill checks the box. However, as I mentioned previously, CAA SA (in Dakar) will obtain BRC certification within 12 months and we’re hoping to be able to take a portion of our fonio directly to customers from the Dakar facility.”

Q: You spoke earlier about making a positive impact on the local communities and environment with the fonio project. How have Terra’s partnerships with locals in Mali, Senegal and other West African communities improved the lives and livelihood of food producers, while also improving the value provided to their CPG (Consumer Packaged Goods) customers?

M: “I would say that one positive impact we’ve had so far would be an expansion of acreage. What we realized was that there were a lot of people in the villages who had additional land, but there was no market for any grains so they wouldn’t use it for farming purposes. Now, due to our work with fonio, it has allowed them to use that land that was previously sitting idle for fonio production. These villages and farmers now have a consistent (fonio) market that did not exist before we got involved.

Also, the nice thing about fonio is that it has a short crop cycle. This means that it can be harvested sooner than other comparable grains like rice, and thus, farmers can earn an income quicker. In some cases, fonio crops have even produced multiple harvests in a single year, although this can’t always be counted upon. This short crop cycle is important because in many Sub-Saharan countries, school fees are traditionally due in early October, but far too often there are children who can’t attend because their families don’t have enough money at the time these fees are due. However, fonio can be harvested in September, which allows farmers to generate revenue early enough to be able to pay the school fees for their children.

What has happened before with crops like corn is that corn is only available to be harvested in October/November. So, by the time the money is paid, one or two months of school would have passed and for some families that would mean their kids would not be able to go to school at all. Unfortunately, you can’t send your kids to school in these regions until you pay the school fees. It’s small things like that, things you or I probably wouldn’t usually think about, that have made a big difference. Hopefully we can continue on that trajectory and increase the opportunity for people to create their own economic activity through the cultivation of fonio.

For the CPG Customers, it’s mainly that there’s so much marketing buzz on social impact and greenwashing, that to actually consume a grain or a food that is not only nutritious and genuinely good for your health, but also has a direct positive impact on the people and their communities where it is harvested, that is quite unique.

I agree with Peter (Carlson, Director at Terra Ingredients), who coined the fonio project and the work we’re doing as the “win, win, win” scenario—meaning that the farmer, supplier and consumer can all enjoy a positive outcome from the methods we’re enacting. This is particularly fun for me, because it’s not the mass farming story with industrial techniques that can often harm the environment and push out the people who originally inhabit it. It’s proof that you can actually do good with the food that you consume. Hopefully, we’ll get wider recognition and more people will know about fonio in the near future, because the more the demand is growing, the more we can expand or add villages to the program and have the same positive impact elsewhere.”

Q: Fonio, specifically in Europe and even some African societies, has been given the moniker of “hungry rice”, largely due to a lack of knowledge around the crop’s uses and its role in African culture. How are you working to destigmatize fonio as “hungry rice”?

M: “It’s funny, fonio is generally seen as a grain that is mostly used during weddings, ceremonies and other festivities in the communities where it is grown. What plays to this stigma is that fonio is widely known within certain ethnic groups in those African countries, but not known by others.

For instance, if you look at Senegal, in the east, or the southeastern parts of the country, whether it’s Fulani or Mandinka ethnic groups that live in those areas, fonio is a staple and it’s just part of their diet. However, in Dakar, where it’s dominated by other ethnic groups that didn’t grow up with fonio, you wouldn’t believe it, but there are actually a lot of Senegalese who don’t know what fonio is because it’s not part of their diet. So, you sometimes have this divide between the more rural communities where fonio is primarily grown and consumed, versus the urban populations that may never have encountered it previously.”

Q: To that point, do you think destigmatizing fonio as “hungry rice” will be a big challenge as far as marketing and informing consumers? Or, do you think that will be easily resolved when you simply show them the data and the nutritional info?

M: “Very easy. It’s actually already started to shift, because people are getting more health conscious and there’s a bigger movement in several West African countries to “buy local”, instead of just importing food. All of these trends are leading to a rejuvenation of local grains, with fonio being one of them. It was only 20, 15, and as recently as 10 years ago that you wouldn’t have found fonio anywhere in Dakar restaurants, or really anywhere else beyond the small villages where it was farmed. Now, however, the high-end restaurants and hotels have fonio on the menu with a lot of local cuisines. You’re starting to find that the access to it is much easier because there’s a demand for it now and people are actively looking for it.